Thinking Theatricality

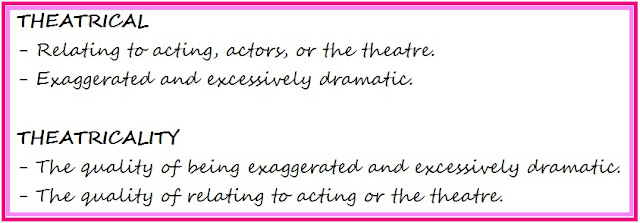

It is interesting that in the Oxford English

Dictionary definition of the two terms, Theatricality emphasises the more

negative association of the term, rather than the aesthetic connotation.

Theatricality, as a notion, relates to lies and falsehood, all the way back to

Plato’s suspicion of mimesis. Even Nicholas Ridout writes that there is ‘an

antitheatrical prejudice within the discipline of theatre studies itself.’[1] And

Stanislavski urged his students to ‘act simply and naturally, without

theatricality.’[2] But even to ‘act naturally’

in a theatre production is still theatrical as the self of the character is not

the self of the actor. They are not-not-I[3],

which is a theatrical device.

While both Theatricality and Performativity are fluid

terms and resistant to a singular definition, I found clarity in the writing of

Josette Féral who writes that ‘Theatricality seems to be a process that has to

do with a “gaze”…’[4] that semiotically reads

the space, recognises the ‘other’ and allows theatricality to takes place in

the gap between the self and other. It is a result of either a body (the other/an

etic view) claiming the space as a theatrical space, and/or a spectator (the self/an

emic view) framing a performance or performative as a theatrical event. This

imposition on the performer, the other, can happen willingly, as in the case of

an actor acting, or unwillingly, as in when the spectator impose a theatrical

narrative on an event or action.

Our attempt at coming up with some definitions or explanations of Theatricality

Theatricality is, therefore, found in the space of

spectatorship: when an action or performance is deliberately interpreted as

removed from the quotidian.

Image Source: autoevolution.com

Davis and Postelwait posit that ‘Theatricality is […]

a way of describing what performers and spectators do together…’[5] Theatricality

is a relationship – a spectatorship. Does this mean that theatre, and

theatricality is ‘more true’ because it relies on this bearing witness?

Theatricality is, at least, a conscious choice imposed on a body (emic or

etic), aware of its falsehood, aware of its own performance, rather than

performativity which appears to be, in part, unconscious.

Reinelt writes of ‘theatre’s capacity for creating

a new real, making manifest the real, embodying the real…[and]… Theatrical

tools can be useful for decoding social reality…’[6] which

reflects Victor Turner’s cultural feedback loop. Theatricality provides us with

a model for performativity, and theatre can provide us with a blueprint for

social action.

Image Source: fandbnews.com

Writing of rituals, the display of emotion at grand

events, parades, etc. Reinelt states that ‘It seems clear that the public life’s

theatricalization is no longer a contested issue’.[7] We

prize theatricality over ‘reality’, the falsehood over the truth, and

entertainment over evidence. However, Ridout writes that ‘In becoming aware of

this framing up we are invited to see what lies not outside the frame but

beneath or within it…’[8] Theatricality

is an awareness of falsehood, which invites us to look for the truth beneath

it. Only by framing the theatre as separate, as ‘other’, can we recognise what

is outside it, and recognise the ‘self’.

[1] Nicholas

Ridout, ‘Introduction’, in Stage Fright,

Animals, and Other Theatrical Problems (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2006), p.15.

[2]

Stanislavski, quoted in Tracy C. Davis and Thomas Postlewait, ‘Theatricality:

An Introduction’, in Theatricality,

ed. by Davis and Postlewait (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University

Press, 2003), p.21.

[3][3]

Richard Schechner, ‘Restoration of Behaviour’, in Between Theater and Anthropology (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 1985), p.112.

[4]

Josette Féral

and Ronald P. Bermingham, ‘Theatricality: The Specificity of Theatrical

Language’, SubStance, 31.2-3 (2002),

p.97.

[5] Tracy

C. Davis and Thomas Postlewait, ‘Theatricality: An Introduction’, in Theatricality, ed. by Davis and Postlewait

(Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p.23.

[6]

Janelle Reinelt, ‘Towards a Poetics of Theatre ad Public Events in the Case of

Stephen Lawrence,’ TDR: The Drama Review,

50.3 (Autumn 2006), pp.71-83.

[7] Ibid.,

p.71.

[8] Nicholas

Ridout, ‘Introduction’, in Stage Fright,

Animals, and Other Theatrical Problems (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2006), p.13.

Comments

Post a Comment