Sights on Site

Site-specific performance is most

often understood as work which takes place outside of a traditional space of

performance. But how specific can site be?

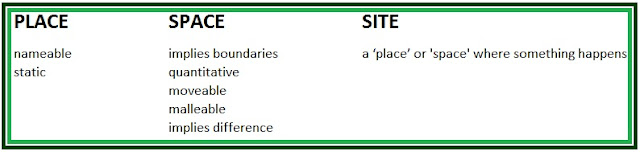

We tried to come up with some ways of understanding the different terms, which are often used interchangeably

In our seminar this week we discussed

examples of work that we could consider to be site-specific work. One piece was

a company who brought soil from another country into a performance space: through

the re-placement of the soil, could the work could be considered to be taking

place there, in the same way that embassies are considered to stand in for the

soil of their respective countries? However, we then also discussed this in

terms of theatricality: how do we know that the soil is actually from the

country of origin? We are told, so we believe, and we allow it to stand in for

the site.

Another example was a piece set around

canals in order to represent a flooded world, or a performative bus tour of a

specific city. Works like these explore the site and the space of conflict

between official knowledge, lived experience, and potentiality. However, both

of these examples have been transplanted to other places, so is the work truly ‘specific’

to the site? Is this truly site specific or is it site generic? Site conscious

or consciousness of site?

We actually found it comparatively difficult

to think of many examples that we had personally experienced. This could be

because of un-acknowledgement (as in the case of Invisible Theatre, maybe we

didn’t realise work was taking place), or maybe because not much true site

specific work takes place (restrictions, permissions, and readily available

space).

Image Source: jonanthonyart.com

Interestingly, when I did a Google image search for Site-Specific Performance, most of the pictures were from performances in art galleries.

Interestingly, when I did a Google image search for Site-Specific Performance, most of the pictures were from performances in art galleries.

Levin writes that, in site-specific

work, ‘the physical site comes alive […] in a complex process of reciprocal

animation […] humans can be said to exist in the midst of a performing world’.[1] The

site informs the work, but the work is, in turn, informed and influenced by the

site. It creates, but also limits, the work to its space (and therefore boundaries),

and the site functions as a character in the work alongside the traditional

theatrical trappings.

We realised that we had mainly

experienced site specific work when we had actively sought it out – as consumers.

Therefore does work of this kind subvert or sustain the mainstream? Even site

specific performance, which by its nature is ephemeral, needs validation (i.e.

capital, or recognition by an institution) as in the case of Small

Metal Objects which was produced by Barbican. Even Graffiti, which is site specific

art, responding to the local area, has gained recognition as an art form, so

can it truly be considered subversive now?

Image Source: thisiscolossal.com

How do we understand and respond to

site? Site has history: people MAKE a site and imbue it with their own

meanings. Even a ‘non-site’ could bear meaning for some people: I have a friend,

whose now husband, proposed on a street corner under a lamppost because that

was where they met for their first date. This non-place has meaning for them.

Levin writes that ‘our perception of

environment is filtered through language, ideology, and memory […] the streets

themselves have their own stories, cultures, politics.’[2] Site

reinforces its own identity, by existing prior to, and after, the art.

Peter Brook famously asserted the

theory of the Empty Space: but no space is empty.

[1]

Laura Levin, ‘”Can the City Speak?” Site-Specific Art after Poststructuralism’,

in Performance and the City, ed. by

D.J. Hopkins, Shelley Orr, and Kim Solga (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009), p.240-4.

[2] Laura

Levin, ‘”Can the City Speak?” Site-Specific Art after Poststructuralism’, in Performance and the City, ed. by D.J.

Hopkins, Shelley Orr, and Kim Solga (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009), p.248-52.

Comments

Post a Comment